The Importance of Developer Experience - Developer roles are evolving!

11th September 2021Introduction

Over the past five years, I have had the pleasure of working within different developer communities within various organizations. These experiences are where I captured my passion for developer experience and Dev(Sec)Ops. Making life as easy possible for developers and ensuring the right tools are in place is essential to improve developer retention and business outcomes. Nowadays, this is even more imperative because the role of a developer is no longer just software development; it's starting to become key within every area of the SDLC.

The evolution of a developer ...

What do I mean by this? Let's quickly discuss the evolution.

Traditionally, a business analyst would hand a requirement over to a developer. That developer would then carry out the software development of that requirement. The developer would then hand it over to a tester to write unit tests, regression tests, etc. You would repeat that process until all requirements are completed. Then, a security engineer would run a security test, and they would attempt to understand which are false positives and need to be fixed. Once all vulnerabilities are solved, quality would come in and work with the business/technical analyst to ensure all documentation are complete. Then, you can release!

What's a theme you are seeing out of this way of working? It's very waterfall, messy and there are so many opportunities that can slow the release.

Now, a more modern approach could be:

A scrum master works with a developer to draft user stories that meet the requirement. The developer would carry out the actual software development. Once complete, they would then write unit tests (maybe even UI tests if it's a GUI and some regression tests). Alongside testing, the developer gets SCA and SAST reports of any vulnerabilities, fixing them during development if any arise. Additionally, the developer is updating design documentation, README's, CHANGELOG's, etc. During this process, the security engineer, quality consultant, business/systems analyst is ensuring its meeting requirements (DevSecOps), meaning just before release, there are no problems, and you can release straight away!

So, what's the main difference you see between the two? Straight away, you see the developer (or developers) are carrying out a lot more of the tasks within the SLDC lifecycle. This doesn't mean the other roles aren't involved or important; it just means there is a shift in perspective from who is primarily doing the work. You may still have testers for large applications, but the developer developing the feature/bug request is writing the initial tests. Similarly, you may (and should) have a dedicated security engineer on hand to assist with vulnerabilities that the developer needs advice about. Still, the developer is going in and remediating the vulnerabilities. These two examples highlight the shift left in nature (nothing new) in how development is done.

Why? Why is this evolving in this way? Let's discuss:

- The most important one is, the developer knows the codebase the best. I'll give two examples of why this is critical:

- Let's say you have a centralized testing team that provides unit/regression/UI testing capabilities. The developer does the work; they hand off to a tester to write the test(s). There is a one-two day SLA for that testing to be picked up. Then the tester has to get up to speed with the feature/bug that has been written/fixed. The SLA largely depends on the size of the change but can take anywhere from an hour to a day. The actual development of the tests likely take the same amount of time, so no added time there. The work then gets PR'd, which needs another review by the developer who wrote the code to ensure it meets the requirement of the bug/feature. Again, adding to the total SLA. In comparison, if the developer who wrote the code write the tests as well, there is 0 SLA in the handover between the testers, 0 SLA in getting up to speed with the codebase and 0 SLA in the review, as the tests can go into the main PR into the dev/qa/main branch. Think about this at scale; there is SO much time saving, which equates to quicker value for the business.

- Another example, security. Traditionally, a security person would look through a report and say, "Hey, you need to fix all critical and high vulnerabilities". The developer would pivot the conversation to fixing the vulnerabilities that had the highest risk on the most critical part of the codebase. However, the conversation would typically end in all critical and high vulnerabilities needing remediating, if not all of them. Although controversial, this is highly inefficient and generally wastes a considerable amount of time. Why? Just because a vulnerability is flagged as critical, it doesn't mean it's critical to your application. On the other hand, you may have a medium severity that directly affects the most important aspect of your application, with the highest surface area. This is why the developer who wrote the code takes accountability for reviewing and remediating the vulnerabilities of most criticality to the application, not based on the potential effect. This leads to quicker release cycles and more secure software as developers fix vulnerabilities that count early!

- The second reason developers are becoming more involved is due to more and more aspects of the SLDC ... well ... they are becoming code. Think about traditional development; you would build software and hand it off to an infrastructure person to deploy it. Nowadays, the developer is that infrastructure person. The developer writes the code for the feature but then writes the code for the IaC, which supports that feature. You are also seeing CI/CD becoming more config as code. Like the feature example above, the developer writes the feature, then the IaC, and any additions to the CI/CD landscape. More and more aspects of development are becoming code, which requires a developer.

So, the above talks about the evolution of a developer, which paints a picture of why developer experience is so important. If the developer is doing more, you naturally would like to maximize velocity to get the best value. However, most importantly, you want to maximize how happy they are. A happy developer = better retention + productivity. I truly believe the more emphasis you put on developer experience, the more you will get back. So, what can do you do to improve the developer experience? Below, I will discuss my three core principles when it comes to developer experience.

Developer First Toolset

Stand up tooling that has developer-first principles. When you put more on developers and follow a DevSecOps approach, it's critical to stand up tooling within the toolchain that focuses on developers.

More and more tools are starting to put developers at the heart of what they do, which paves the way for increased productivity and experience (we have discussed why this is important above). Some great examples of tooling which should be developer-first are:

- Security

- CI

- CD

- Quality

- Testing

You wouldn't hand a scientist equipment that didn't make it easier for the scientist to use? You wouldn't have a medic devices that were hard to use and make their life hard? So why would you hand developers tooling that doesn't make the life of a developer easy?

If you're a company looking to change the tooling to be more developer-focused, ensure you have developer(s) involved in the decision making.

Frictionless Processes

Focus on the process, not just the tools. Having the right tools are essential, but if you make them hard to use or implement them in a way that introduces friction, you won't be getting the most out of the tools. What can you do to ensure you have good foundations?

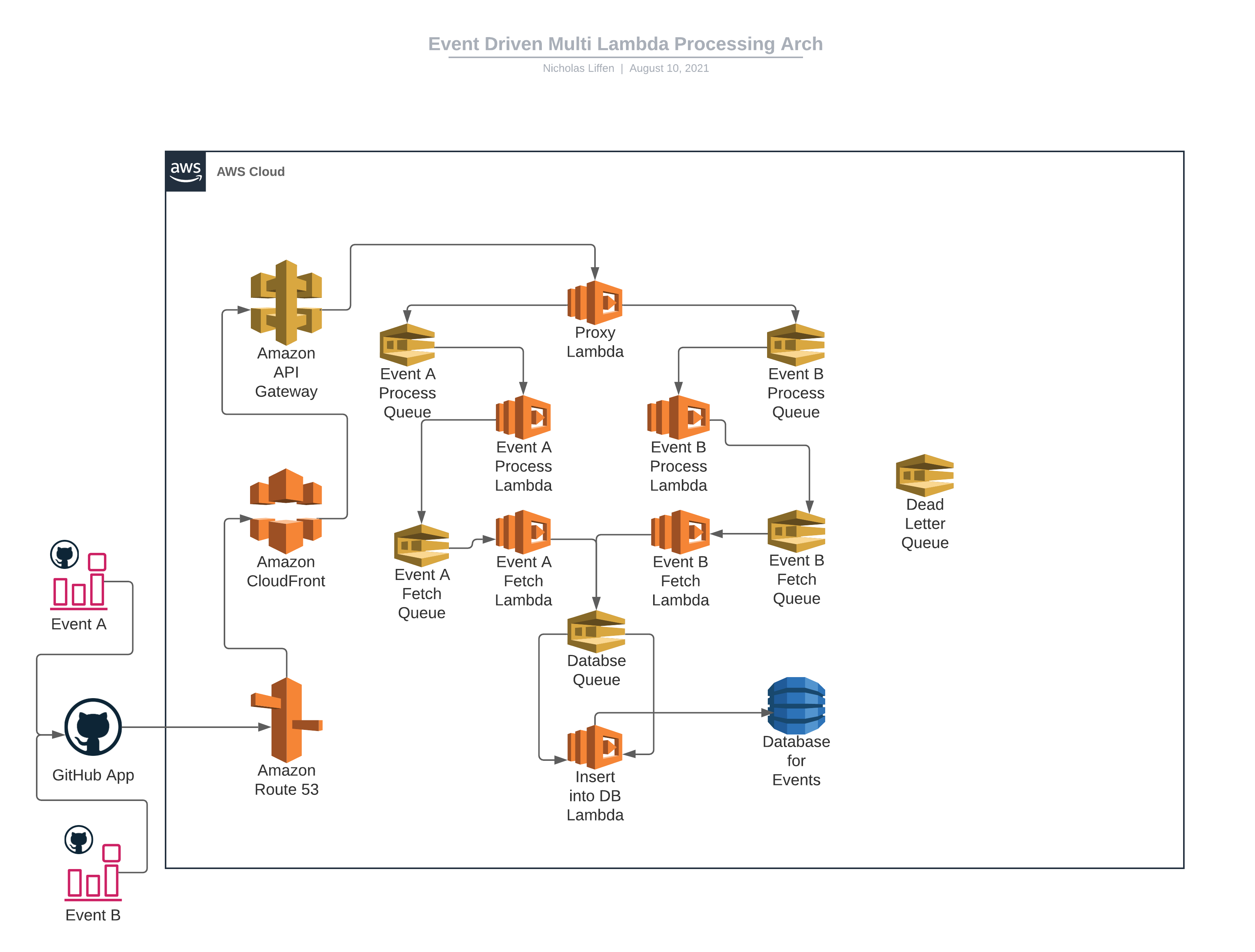

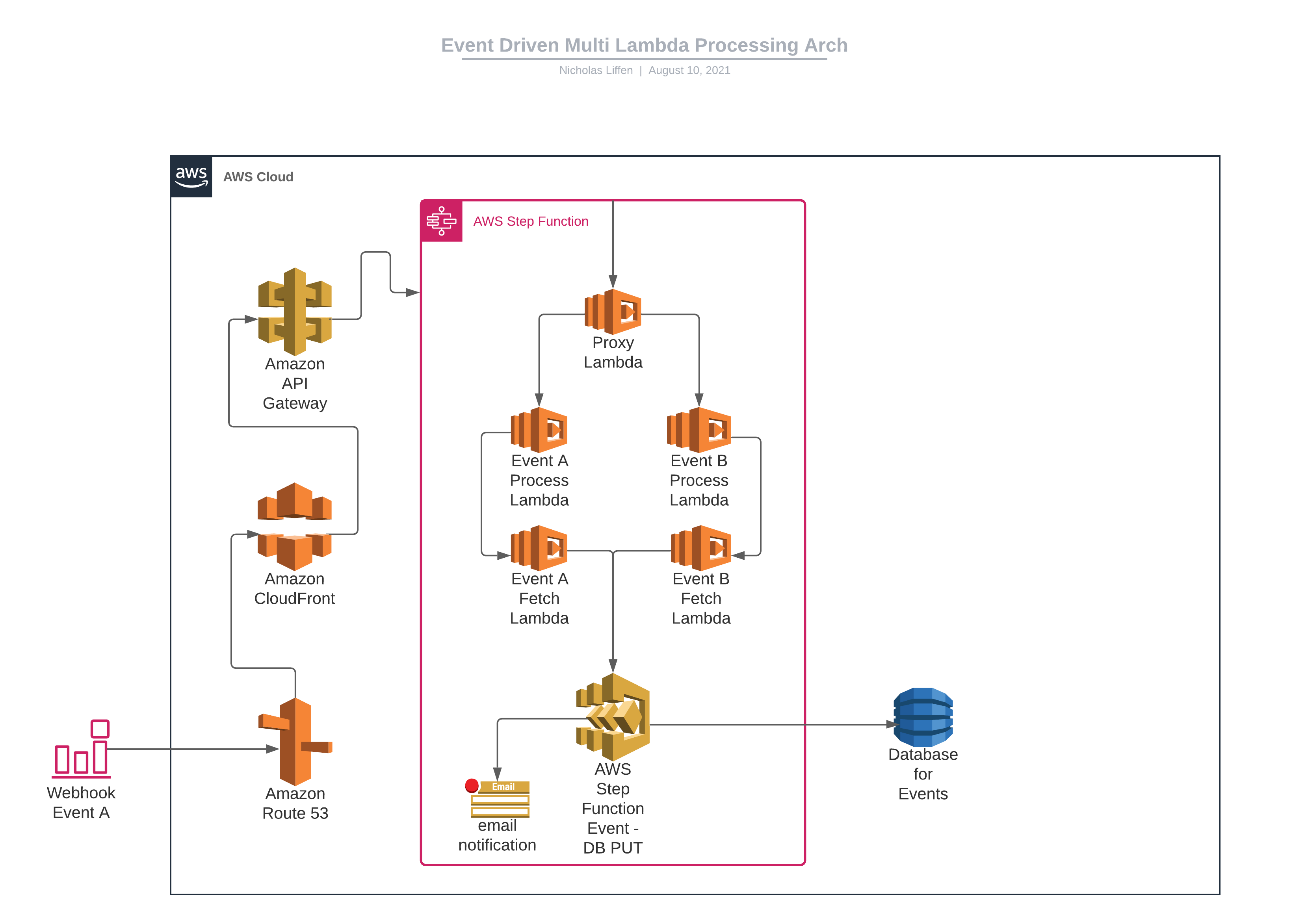

- Automate: Try not to put any manual requests or SLA's on setup. Use the API's, Webhooks, etc., provided by tools to get set up in an automated fashion.

- Provide suitable levels of access: Try not to limit access to tools, especially for the reason of just in case. Provide people with the autonomy to read, write and administer their solutions. There are times where you have to limit access, especially in large enterprises, but do so for the right reasons, not just for the sake of not knowing.

- Open API's: The most frustrating thing for a developer is when they are restricted on the art of the possible because API's are disabled due to the team managing the tooling worrying about what teams may do, which they don't know about. As above, there may be good reasons (security, etc.), but unless something is blocking you, open API's and empower teams to be creative.

These are just a few examples. The main point to get across is automation. Automation is a great way to unblock friction. It is especially important regarding the DevOps Toolchain. Ensure that it's easy to get data between tool A and tool B. Automation and interconnectivity are essential to success, whether that's a testing tool to a project management tool or a security tool to a CI tool. Ensure you think about your process, not just the tools.

Empowerment & Trust

The last one focused on empowerment and trust. This behaviour generally gets overlooked, as it's easier to focus on the tools because you can measure and quantity success easier. However, there are simple steps you can make to help drive a more open culture among developers:

- Don't push back on developers for the sake of wanting to share an opinion. I have seen many scenarios where a developer shares a great thought but gets questioned or disputed by someone who doesn't know the area but wants to share a thought to make sure they are in the conversation. Everyone should share ideas, collaborate, and be open, but ensure developers voices are heard and listened to. This is a simple behaviour you can adopt but will make a huge difference.

- I mentioned this above in the process section, but nowadays (especially in larger enterprises), access is restricted, API's are disabled (and I know what you're thinking, but what about security? It would be best to never compromise on security, but think about what automated processes you can use to keep to a high standard of security but still enabling access and API's). E.g. key rotation, automatic access reviews, etc. The more you give to a developer, the more they will feel empowered and trusted, which will boost morale.

Focus on your people, and have trust in your developers.